Is behaviour the problem or the symptom? In this piece I urge senior leaders and indeed society to stop seeing the bad behaviour as the problem. Service level observations simply lead to service level responses. A deeper and more meaningful dive is needed into the culture and ask (1) Why, despite the many reports into police behaviour we continue to see harmful behaviours and attitudes on open display and (2) Why many officers continue to remain silent when they observe such behaviour. Finally I suggest police leaders require to learn from decades of social science that help understand why good peole often do bad things

Workplace culture isn’t built on soundbites or promises. It’s built on consistency, communication and effort. It might start with senior leadership but it definitely doesn’t end with senior leaders. Culture is never neutral, its good or bad. Culture is the weather system of any organisation and happens with or without leadership. So, to leadership you might as well get involved.

Why is culture important? Simply because it is. When a bad culture is captured on camera it truly looks horrible. Whether undercover footage from a residential home, a care home or a police station, viewers get a front row seat to the mistakes and the misconduct committed by people within. Such footage leaves it mark, and trust in these institutions suffers. My old profession of policing continues to haemorrhage trust and whilst we appear happy to focus on those that cause harm we seldom commit to a deeper, and a more meaningful exploration of why such behaviour occurs in the first place and why it continues.

I first met the late American psychologist Phillip Zimbardo in 2018 having previously read his book, The Lucifer Effect some years previously. As a member of the Scottish Violence Reduction Unit between 2009 until I retired in 2017, I became fascinated with the why. I had spent most of my policing career simply focusing on the who. As I quickly learned, the who is the easy part. Zimbardo’s book took me down a rabbit hole focusing me on the individual, the situation and the system. I continue to this day fascinated with what the journey has taught me.

My short time with Zimbardo allowed me to explore his now infamous ‘Stanford Prison Experiment’ that forms the backdrop to his book. Whilst itself heavily critiqued, it still to this day, provides an insight into how seemingly decent people, when given the power over others, quickly demonstrated control and abusive behaviours whilst clearly adopting an ‘us and them’ outlook to those they were supposed to be looking after. Zimbardo himself shared that it was his then girlfriend that threatened to ‘dump’ him if he didn’t stop the experiment. He himself had become a passive bystander to the harm he had seemingly created. He stopped the experiment and the rest as they say was a happy marriage.

Zimbardo was not alone in influencing good people to do bad or wrong things. Another American psychologist, Stanley Milgram in 1961 wanted to explore the defence provided by Nazi’s at their post WW2 trials in Nuremburg, “I was only following orders”. A quick aside, did you know that Milgram and Zimbardo went to kindergarten together. I laughed when Zimbardo shared that with my small group. That must have been some playground pair don’t you think? Milgram’s obedience experiment showed that participants were willing to deliver what was perceived to be dangerous electric shocks to strangers simply because they were told to by some who looked like they were in charge. Milgram himself was shocked at the results.

There have been other experiments that demonstrate that when placed in the right situation, individuals are influenced to go along with others, even when actions are clearly wrong. When we align these experiments, we begin to see a fine line between good and bad. In a recent piece written by consultant psychotherapist Des McVey he suggests this fine line when he states that human behaviour is not fixed.

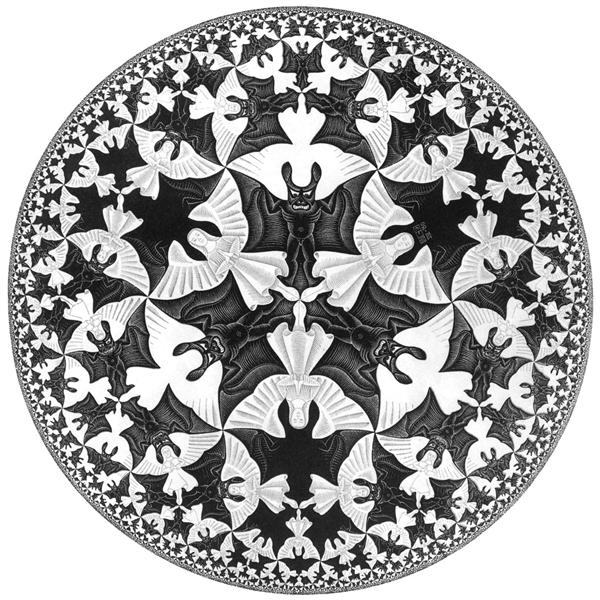

The image below is artist MC Escher’s Circle Limit IV. This is also referred to as Heaven and Hell or Angels and Devils. Philip Zimbardo discusses the image in his book to illustrate that the world contains both good and evil and that the boundary between them is permeable, and good can become evil, but it is harder for devils to become good.

When we simply focus on the individuals who commit harm, we miss the deeper truth that it is often both the situation and system that plays out on individuals in the settings I discuss above. The situation being the teams and peer groups, the system being the organisation itself.

Last week the BBC’s Panorama team shared some horrific footage that was captured from within London’s Charing Cross Police Station. Undercover reporter Rory Bibb who had successfully gained employment in the custody suite. Let’s be clear that it was whistleblower statements that led to the placement of Rory in the police station by the BBC. That speaks loudly don’t you think? Let’s also be reminded that this station was not new to the spotlight having been at the centre of major police misconduct in 2022 when a culture of misogyny, bullying and sexual harassment was revealed by the Independent Office for Police Misconduct.

As it was in the most recent Panorama programme the focus was simply on those who were committing the misconduct. In his piece Des McVey highlighted the presence of a so-called expert on policing. Former senior police officer Sue Fish was on hand to view the undercover footage, highlighting the unacceptable behaviours she observed. She was right on two accounts. First, the behaviours fell below what was acceptable and secondly how these behaviours would be playing out amongst other staff who would feel powerless to speak up. Remember it’s clear staff contacted the BBC, not the Metropolitan police themselves. I agree with McVey when he states that her insights were ‘astonishingly shallow’. What she failed to talk about and what is hardly ever talked about is the why. I would argue that Fish in her policing career could have focused more on the why as opposed to simply ‘rooting out the so-called bad apples’ which for me has become a fashion statement amongst senior police leaders.

In a recent piece entitled “What Rowley hasn’t yet got right at the Met”, policing commentator Danny Shaw raised searching questions about leadership, supervision and culture. Why is it, despite report after report into misconduct within Rowley’s Met do we continue to see such behaviours on open display both in and outside of the police station. For me to address the many challenges that remain across UK policing the usual responses by organisations won’t cut it. They are often superficial and service level responses. A typical response is the misogyny lecture or the e-learning package on being an ‘upstander’. More focus is needed on the leadership itself. Of course, it must start with senior leadership, but such leadership must trickle down and then back up again. When it comes to culture everyone has a leadership role. Speaking to a colleague who is a victim of harassment by co-worker demonstrates empathy and compassion. Speaking to a colleague about a lapse of judgement, a mistake of poor behaviour takes moral courage. In both situations the staff member is being a leader. As someone who uses a lens of leadership to address harm, leadership is a skill not so much to be acquired but a skill that can be activated in anyone.

How many times have we seen senior policing figures lead a press conference or talk about expectations of behaviour within their organisation. Whilst important, it’s clear many of them fail to fully understand why, that despite their demands, do junior staff still behave so badly. For me leadership at the top levels of policing fail to fully understand the group dynamics that are at play, and they fail to create the systems that both prevent staff from acting in such a way and supports staff to do their bit in preventing the harm being done. The kicker for me is that all these senior leaders have been there. They have all had day one in the job. Why now do they appear to forget this? Another reality is that most staff want this type of supportive culture. I see this in every training I’ve delivered to police officers at all levels.

Leaders at all levels in likes of policing and indeed in all other similar high-stake settings must begin to better understand the daily realities of fear, the risks of group conformity, and obedience. I remember a few years back speaking at an event attended by many senior police officers and staff including the organisations Chief Constable. I introduced the Milgram experiment into the session and took the group through the set-up of the experiment, the different variations of what happened and the results. I do this frequently when working with the likes of the police. I work to back up everything I saw with evidence because I know this works best to influence human behaviour and engagement. At one point the Chief shouted, “I love this experiment”. I really wanted to say to him “if you really like this experiment then why aren’t you using the learning from it to support your culture”, I didn’t.

The likes of Stanford and the Milgram experiment present so much learning. Milgram highlights the power of authority figures over the actions of people who are, or think they are under their command. In likes of policing, the issue is typically not the use of authority to direct an officer to harm someone, but rather how authority can inhibit the actions of others to intervene when any form of harm is observed. This was clear in the Panorama programme when it was the sergeant behaving badly. Remember hierarchies aren’t always formal ones, rank, grade etc. They are informal as well with age, service and role playing out.

Zimbardo’s work highlights the realities when staff in likes of police are given roles that involve exercising power of others. As Zimbardo found, in such situations there are ever present dangers. Fear being the biggest. Fear of losing control, fear of violence and fear of going against the group or being seen as weak. When leaders fail to supervise such groups the fear manifests itself in bad behaviour and silence.

Compassion fatigue is a sickness and is emotional and physical exhaustion from prolonged exposure to others’ suffering, leading to reduced empathy and effectiveness. In policing, it can occur when officers repeatedly deal with trauma, violence, and victims in crisis. Over time, they may become desensitised, withdrawn, or emotionally numb, impacting their judgment and interactions with the public. This can lead to burnout, mental health issues, or misconduct. Compassion fatigue not only affects officers’ well-being but also erodes community trust. This isn’t simply academic fact, it’s a daily reality in high-risk settings.

The realities of what I discuss above, impact far wider than just on the individuals involved. The profession of policing is affected. Relationships between leaders and staff and amongst all staff will worsen. The resultant well-being issues that such events contribute to will impact on the core policing role, so communities will therefore be affected also. Ask any officer why they join the service? They don’t join to get rich, that’s clear. Most join to help people and to make a difference. Police culture is currently getting in the way of this aim.

The Panorama programme presents policing in the UK with a reminder of the issues and challenges that remain. However, it also presents opportunities to prevent future harm. I agree again with Des McVey when he suggests that the likes of policing require to stop treating junior staff as expendable. For me the following is suggested.

- Senior leadership must now begin to operate as organisational stewards that begin to create trust, both within the profession and from the communities it serves. This means moving beyond task management to cultural leadership which intentionally cultivates culture.

- Senior leaders require to be trained in the psychology of power and conformity. I would recommend that all senior leaders read The Lucifer Effect. If you love the Milgram experiment read the learning and how it can better support, you, your officers and your communities.

- The promotion of leaders at all levels who have emotional intelligence, self-awareness and self-regulation. Instil responsibility on them. Leadership is about love and connection, not simply being technically good. Remember we not only need good police officers, we need good human beings first.

- Steward the organisation, not just the crisis. Many policing organisations are caught in a freeze response. The past years and the numerous scandals rightly demand action however these issues also reflect an internal crisis where poor wellbeing is playing out. Don’t be quick to react to events. Ask why. Whilst some officers need to lose their jobs, not all do.

- Become more generationally aware. Today leaders are leading a workforce that spans four generations with each bringing different motivations, expectations and relationships. Staff across these generations bring diversity in ideas, worldviews, experiences and purpose. Leaders cannot rely on their past experiences as they progressed in their careers.

- Instil cultural responsibility in all staff. Help them see the benefits of taking responsibility. There needs to be observable benefits for everyone, not just victims of harm or communities. The costs to many are clear. The costs inhibit early action. When benefits outweigh costs the science says people act.

When senior leaders fail to lead, the cost is high. Staff will disengage; apathy, learned helplessness, low morale will become daily realities. Without intentionally culture driven leadership the void will be filled by resistance, low expectations, high sickness levels and poor behaviour excused as ‘banter’. Recruitment and retention will also be a challenge. There is a growing recognition in that staff wellbeing cannot be limited to a daily exposure to traumatic events. The deeper and more chronic source of daily stress is from the experience of working in the organisation. The National Policing Institute in the US recently stated “Officers perceptions of organisational stresses far outweigh operational stresses on the job, and these have been linked to a variety of adverse outcomes including poor health, quality of life and performance as well as psychological distress and sleep problems”

Let me end by using the final lines within the Des McVey piece –

“Until we accept that frontline misconduct is not the problem but the symptom, we will keep failing staff, and in turn they people they are meant to care for and to serve”

What I have shared I suppose is a call to action. As a leader you can get involved or simply get out of the way.